Healing Living with limb loss is a profound life change that affects the body, mind, and daily routines. For some amputees, this transition can intersect with hoarding behaviors—creating challenges that are often misunderstood and rarely discussed. Hoarding is not about laziness or lack of willpower; it’s a complex mental health condition that deserves empathy, especially when layered with physical disability. Supporting amputees who struggle with hoarding requires a thoughtful, trauma-informed approach that balances emotional wellbeing, physical safety, and long-term independence.

Understanding the Connection

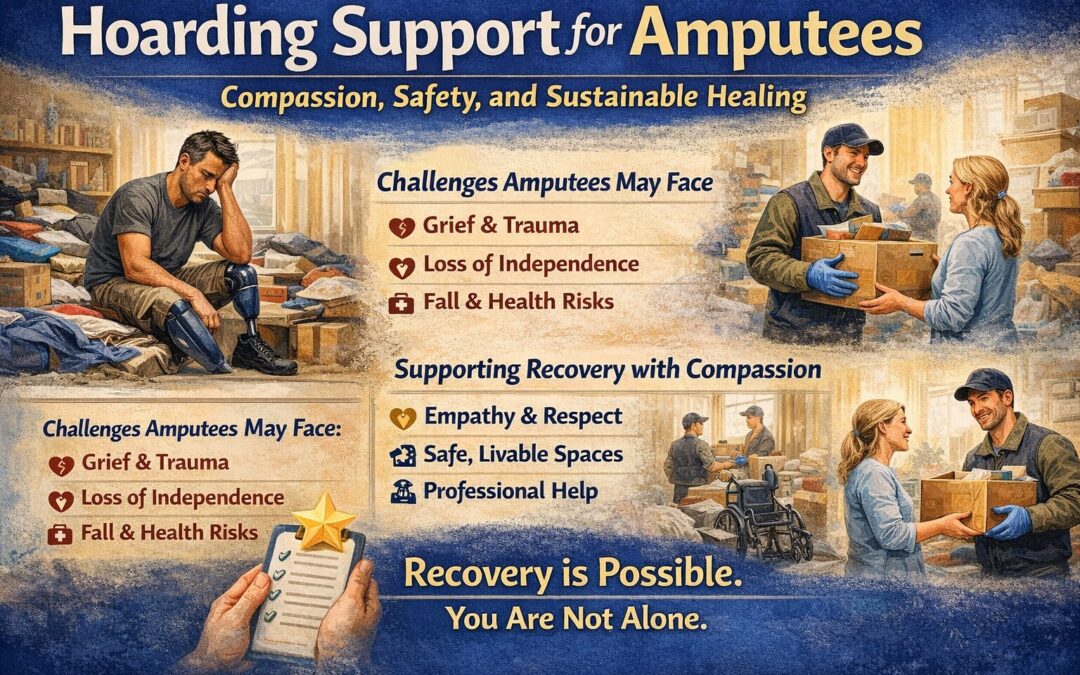

Hoarding disorder is frequently linked to anxiety, depression, trauma, and major life disruptions. Amputation itself can be traumatic, whether due to injury, illness, or congenital conditions. The loss of a limb may also bring: Grief and identity changes Reduced mobility or chronic pain Fear of future scarcity or vulnerability Loss of independence or control For some amputees, keeping items can become a way to feel safe, prepared, or emotionally anchored. Objects may hold memories of life before amputation or represent a sense of stability in an otherwise changed world. Recognizing this connection is the first step toward meaningful support.

Unique Risks for Amputees Who Hoard Hoarding environments pose risks for anyone, but amputees often face heightened dangers:

Fall hazards: Narrow pathways, cluttered floors, and unstable stacks increase fall risk, especially for prosthetic users or those using mobility aids. Infection and wound care issues: Unsanitary conditions can threaten residual limb health, surgical sites, or prosthetic fit.

Emergency access problems: First responders may struggle to reach someone quickly in a cluttered home. Prosthetic and equipment damage: Essential mobility tools can be misplaced or damaged among stored items.

Because of these risks, addressing hoarding is not about aesthetics—it’s about health, dignity, and safety.

What Effective Support Looks Like

1. Start With Empathy, Not Ultimatums Shame and pressure often make hoarding worse. Conversations should focus on concern and collaboration, not judgment. Instead of “You need to get rid of this,” try “How can we make your space safer and easier for you to move around in?” Trust is essential, especially for amputees who may already feel scrutinized or dependent on others.

2. Involve the Right Professionals A multidisciplinary approach works best. This may include: Mental health professionals experienced in hoarding disorder Occupational therapists who understand mobility needs Peer support groups for amputees Professional hoarding support or cleanup teams trained in trauma-informed care Importantly, cleanup should never happen without the person’s consent and involvement whenever possible.

3. Focus on Function, Not Perfection The goal isn’t a magazine-ready home—it’s a livable one. Priorities might include: Clear, wide pathways for prosthetics or wheelchairs Accessible bathroom and bedroom spaces Safe storage for medical supplies and mobility equipment Reduced fire and fall hazards Small, functional improvements can dramatically increase independence and confidence.

4. Go Slow and Celebrate Progress Hoarding recovery is not linear. For amputees, energy levels, pain, and mobility limitations may mean progress happens in short sessions over time. Celebrate wins—clearing a single walkway, organizing one drawer, or safely discarding a small group of items.

Progress measured in dignity and safety matters more than speed. Supporting Loved Ones and Caregivers

If you’re supporting an amputee who hoards: Listen more than you speak Avoid secretly discarding belongings—it can be deeply traumatizing Encourage professional help without forcing it Take care of your own emotional wellbeing too Caregiver burnout is real, and you don’t have to do this alone.

A Message of Hope

Amputation and hoarding are both deeply human experiences rooted in survival, adaptation, and emotion. With the right support, amputees who struggle with hoarding can create safer, more functional living spaces without losing their sense of control or identity. Recovery is possible. Dignity is non-negotiable. And support—when offered with patience and respect—can change lives.

Recent Comments